TUSLO AND FUTURE OF EUROPE

CLICK ON THE LINKs BELOW TO REACH THE ETUC PRIORITIES IN THE PLATFORM ON THE FUTURE OF EUROPE

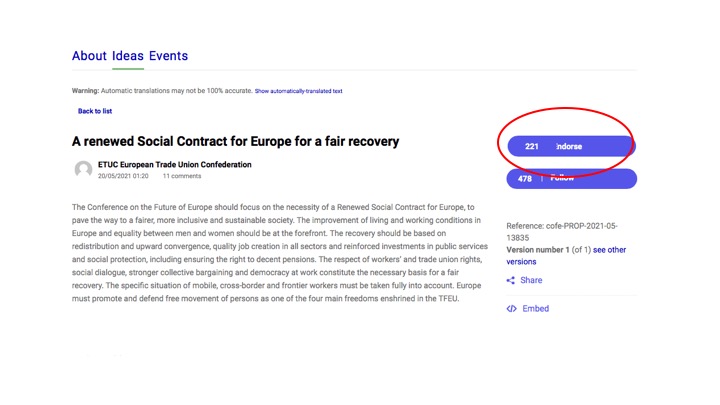

A renewed Social Contract for Europe for a fair recovery

New EU economic model and governance

European Pillar of Social Rights for a social market economy

WHAT TO DO:

- REGISTER IN THE PLATFORM (SEE ETUC TUTORIAL) https://futureu.europa.eu/?locale=en

- “ENDORSE” THE IDEA

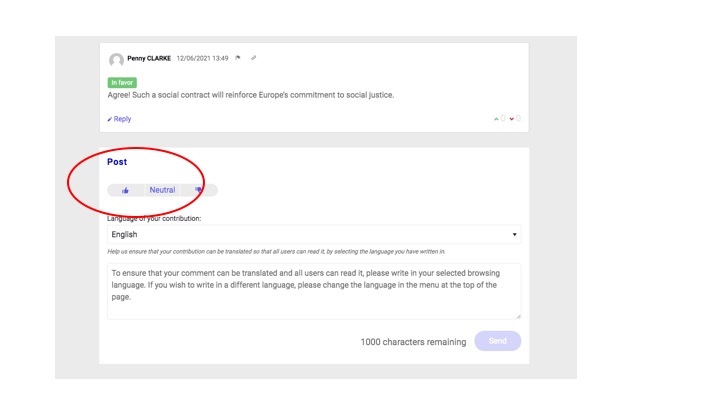

- LEAVE A COMMENT IF YOU WANT

- REMEMBER TO CLICK ON “THMB UP” IF YOU LEAVES AN IDEA

FAST TRACK: DO YOU WISH TO LEAVE A COMMENT? PICK UP A SENTENCE FROM HERE

European Pillar of Social Rights for a social market economy.

Pick up a sentence from https://est1.etuc.org or chose one below

Article 1: Ensuring that quality and inclusive education, training, and lifelong learning be a right and equality accessible for all learners and workers is crucial. 52 million adults in Europe are low-qualified and several countries one third of the workers have very low level of basic literacy and numeracy skills. Upskilling and reskilling of the adults in Europe is therefore a social responsibility and the unemployed and the workers need effective support with.

Principle 2: The ETUC also demands a substantial directive guaranteeing the representation of women from all backgrounds in both executive and non-executive company boards, in a binding quota of 40%. It is also advisable to issue a Guide for implementation of the Work-Life Balance Directive. Such a guide should encourage transposition of the EU Directive through interprofessional agreements in a way that would reduce the amount of time between adoption of the directive and its subsequent application.

Article 3: Access to opportunities more often than not depends on the specific group to which a worker belongs. The objective is to incorporate a policy aimed at removing discrimination (ex-post) along with proactive policies that provide equal opportunities (ex-ante). Reducing protection in the workplace increases discrimination at work. Measures that soften sanctions against unfair dismissals, reduce the power of trade unions (or works councils) in the workplace, or spread non-standard working contracts, weaken the current anti-discrimination acquis that provides for strict sanction systems.

Principle 4: Ensuring that quality and inclusive education, training, and lifelong learning be a right and equality accessible for all learners and workers is crucial. 52 million adults in Europe are low-qualified and several countries one third of the workers have very low level of basic literacy and numeracy skills. Upskilling and reskilling of the adults in Europe is therefore a social responsibility and the unemployed and the workers need effective support within the labour market for fairer technological and green transitions.

Principle 5: The labour market in Europe underwent a huge deterioration in the first half of 2020, this was initiated by the Covid-19 pandemic and the measures taken to prevent the contagion. Workers with unstable, low-paid and/or part time jobs (including undocumented and undeclared workers) were the first to suffer the social consequences of the pandemic.

Principle 6: It is therefore essential to ensure that workers’ rights to collective bargaining and fair remuneration are fully respected in all Member States. It is necessary to set a level playing field within the internal market and trigger an upward convergence in wages. The European Directive on adequate minimum wages plays a key role in this. This Directive needs to ensure that statutory minimum wages cannot fall below a threshold of decency and are adequate, and are defined with the full involvement of social partners. It furthermore needs to increase the capacity of trade unions to bargain for fair wages and working conditions and to tackles union busting practices and it must safeguard well-functioning collective bargaining and industrial relations systems.

Principle 7: As stated above, the Covid-19 pandemic has demonstrated even more that new forms of work need to be legally covered so that workers have access to the protection they need, and that platform workers are recognised as workers. Some measures are already part of this Action Plan, such as the announced legal instrument on a minimum wage and collective bargaining, access to social protection, reducing gender pay gaps or implementing the Recommendation on Access to Social Protection. Besides, the European Commission has announced an upcoming regulation on non-standard workers and workers in platform companies.

Principle 8: Employee involvement in company decision-making processes is at risk due to corporate mobility within the Single Market. Evidence shows that corporate decisions are often taken to avoid employee involvement. For example, flaws in national laws transposing EU directives and, in particular, the recast EWC Directive, impede rights to information and consultation. Sanctions provided in national laws are rarely proportionate, effective and dissuasive. Information and consultation rights do not allow for the involvement and protection of workers. EU legislation should trigger upwards convergence in Europe.

Principle 9: As part of the larger fight against gender-based discrimination, work-life balance is one of the challenges of the century. While the position of women in the labour market is deteriorating, populist forces are turning a blind eye to the difficulty women face in the labour market and in society. Innovative solutions within and without the employment relationship may support households and increase equal opportunities among the working members of a family. SDG monitoring is particularly effective in identifying these gender-based disadvantages.

Principle 10: COVID-19 is the biggest health, economic and social challenge in the history of the European Union. The dimension of Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) is a fundamental part of the European strategy for limiting the spread of the virus and for maintaining economic activities. Numerous national measures have been implemented to fight the spread of COVID-19, also including those appertaining to workplaces and commuting to work.

Principle 11: The majority of Member States underperformed in the EU2020 and Barcelona Objectives. Public investments in this field are decreasing instead of increasing. Poverty among children and opportunities for children strongly rely on the income and social assets of the household they grow up in. It is also important to ensure access to high quality and accessible childcare, together with access to quality education, leisure facilities and health care in order to allow children to fully develop their personality and talents and also workers, particularly women, to be able to fully participate in the labour market, and in the long-term increased equality in society.

Principle 12: The impact assessment of the proposal for a Recommendation on Access to Social Protection aptly describes the challenges behind Principle 12. ETUC made a case for social protection in the 2019 EU Semester providing evidence of the biased approach of the EU, which takes sustainability of national systems as the main, and often, only, policy objective of country specific recommendations.

Principle 13: The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) tends to reduce the adequacy and coverage of unemployment benefits schemes in favour of balancing government budgets, but to the detriment of workers’ protection. Unemployment benefits have nevertheless decreased (replacement ratio, or duration of the benefits, obligations of the beneficiary not linked to participation in ALMP, etc.). The objective of aligning it to a greater extent with Active Labour Market Policies remains valid for a few countries. It is dependent on national models and the EU does not harmonise the performance of activation measures. The consequences of this can be seen in national accounts and poverty rates as part of the benchmarking process within the EU Semester.

Principle 14: The EU exhibits improvements only in combating absolute poverty (material deprivation). However, efforts are not being undertaken to keep people out of poverty or social exclusion: in-work poverty is increasing. The majority of minimum income schemes across the EU are far from providing sufficient coverage, duration and adequacy of benefits. This is resulting in growing social divisions and labour market and economic disruptions.

Principle 15: The needs of an ageing population should be better understood, and solutions found to ensure assistance for older people, adequate pensions, good health and social care and safety nets. Comprehensive social protection systems cannot be built through legislation alone. They need financial resources and a commitment from Member States to make the necessary funds available to move forward in implementing the EPSR. Within this context, the role of the EU is crucial to ensure that people reach the end of their professional careers in good health and with sufficient resources – guaranteed primarily by strong statutory pension systems – to enjoy a dignified retirement.

Principle 16: Health care workers across Europe are working hard to treat and stop the spread of the COVID-19 virus. In many cases, their task is made harder because of staff shortages, inadequate facilities and lack of personal protective equipment and testing kits. The European governing bodies and national governments should take immediate measures to ensure that health services receive much needed emergency funding and to boost staffing levels in the short term.

Principle 17: 80 million people in Europe live with a disability and many are victims of discrimination. For these people, the EU should be a source of augmented freedom and opportunities. People with disabilities face a dire situation in the European labour market, with an employment rate of 48.1% in comparison to 73.9% for the general population. Women and young people with disabilities are confronted with even lower employment rates. These figures, however, do not give an insight into quality of employment

Principle 18: The care sector is crucial to ensuring a decent standard of living for elderly people. It is necessary to improve the attractiveness of the sector in order to raise the quality of the work and services supplied. There is a high incidence of migrants, undeclared and undocumented workers in the sector, especially female migrants. It is important to eliminate all areas of vulnerability for people working in this sector and give workers the opportunity to improve their skills and their working conditions for their own benefit as well as the benefit of users.

Principle 19: Liberalisation and privatisation of public services, including an excessive and non-accountable use of Public-Private Partnerships (hence putting profit above the interests of people) deprive society and most of the population of essential tools to meet their needs. Unmet needs, lack of affordable public structures, and too-costly private provisions are found in crucial sectors influencing Europeans’ quality of life, such as health and care, education and training, childcare and housing.

Principle 20.

Social housing, and decent housing for all households, is a pillar of many social models across Europe. In this regard, and in conjunction with just transitions and the inclusion of the UN2030 Agenda, there should be more emphasis on combating household energy poverty. Member States could take measures (also through the Semester) to intervene more actively in controlling and shaping the private housing market, e.g., through building permits, rent controls, tax on 2nd properties etc., and to prevent speculation.

New EU economic model and governance

The pandemic has changed the global fiscal, macro-economic and social landscape. The EU took measures to mitigate the social impact of the economic contraction, however it is left with high debt, a worrying employment situation and higher vulnerability of large groups of the population. At the same time, the green and digital transformations require huge investments. Demographic trends and uncertainty in the global economic outlook are also part of a new landscape that confirms the obsolescence of the economic governance of the EU.

The ETUC consistently rejected the Fiscal Compact and considers that the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) has to be revised. A new Pact must reconcile the social, economic and environmental aspects of development, building on and creating conditions for the full achievement of the UN2030 Agenda.

We learned that the deepening of the EU integration needs a stronger social connotation. In this regard, and in the aftermath of the Porto Summit on 7th May 2021, the trade union movement is convinced that the new governance has to promote recovery, fairness, sustainability and resilience. It has to strive for a job-rich recovery and aim for full employment, with stable quality jobs (especially for young people) and pursuing upward convergence of living and working conditions of Europeans. It has to be sustainable, removing inequalities and eradicating poverty, in an ecologically friendly way. It has to improve social resilience of our socio-economic models, by fully encompassing the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) Action Plan and building on sustainable growth and decent work.

A social dimension of the economic governance needs a change in the fundamental rules of the economic governance. Art.148 of TFEU is a weak counterbalance to the strength that the Treaty injects in the fiscal, market and macroeconomic components of the economic governance. To remedy this and have a greater impact, the EPSR and its Action Plan, endorsed on the 7th of May in Porto, should exert a stronger role and be integrated in the architecture of the economic governance of the EU.

The recovery strategy provides an opportunity to make the EU governance architecture fairer and more sustainable and to strengthen the EU integration in its economic, social and political components. Stabilisers of public expenditure for investments and social resilience, financed through social bonds, should find a place in the new paradigm of the EU economic governance.

EU taxation should be a tool to rebalance social, environmental and economic objectives of the economic governance, as proposed in the ETUC Resolution: EU taxation and own resources.

It is time to democratise the entire economic governance. It means that the European Parliament should co-decide macro-objectives and policies, supervise their implementation and make the European Commission accountable for results achieved.

Social partners’ involvement will reinforce the democratic value of the European semester and of the RRF implementation. The new architecture should clarify the role of social partners in the processes related to the economic governance of th eEU. The EU Semester and the RRF provide reference to the social partners’ involvement

or partnerships without setting a real binding framework for social partners to be involved.

In a new fiscal framework, which should be implemented gradually, once pre-crisis GDP levels would be reached, room for a golden rule for public investment should

be promoted.

A public expenditure rule could be considered, while allowing automatic stabilisers to operate, whereby investment costs would be distributed over the entire service-life, if debt sustainability is at risk.

The European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) should become a binding component of the economic governance. The social indicators on employment, education and poverty in the EPSR Action Plan, together with the reinforced social scoreboard, should have a greater impact on the economic governance.

The ETUC calls for a stronger involvement of trade unions in the making and implementing of policies that steer the EU economy on track in respect of social sustainability and resilience. In view of the interconnection between different policy frameworks and national plans, the economic governance should establish an overarching principle of partnership with social partners in all areas and processes in which the economic governance of the EU operates; such as the EU Semester, the RRF implementation, the structural funds, the Green Deal, the 14 ecosystems of the EU Industrial Strategy, and the related transformation pathways.

An overarching “partnership principle” should articulate rules for social partners’ involvement at European and national level in all processes belonging to the Economic governance of the EU. At national level, social dialogue should be promoted to ensure social progressive policy frameworks and greater consistency between national plans (National Reform Programmes, national recovery and Resilience Plans, Just Transition Plans, National Energy and Climate plans, operation programmes for structural funds, etc.).

The new governance must support the strengthening of the European industrial base and improve the resilience of the related supply chains. It should also be in line with the concept of “open strategic autonomy” that underpins the update of the EU industrial strategy as well as the review of the EU Trade policy.

A renewed Social Contract for Europe for a fair recovery

It is time to contemplate non-GDP and Green Deal related indicators in addition to sustainable fiscal targets, especially with regard to the current trend in the economic environment, characterised by low inflation and interest rates.

The GDP related reference values for governments’ debt and headline deficit as key determinants of economic policies do not reflect the ambitions of the EU in the economic, social and environmental field. The new architecture should rely far more on non-GDP measurement that monitor the performance of member states on the basis of sustainable well-being, as advanced by social partners in their proposal for “Supplementing GDP as welfare measure” proposed joint list by the European Social Partners, and on inclusive labour market and job security as proposed in the Sustainable Growth and Decent Work

index of the ETUC.

The new economic and social governance of the EU should be based on full employment with high quality jobs and just transition. It should enhance a more inclusive society, fairer income and wealth distribution, and increased public spending and investments, especially delivering quality public care services, education and training, effective social security for all. Furthermore, it should provide adequate minimum protection, especially for vulnerable groups, which should be reflected in the revised social scoreboard.

The Youth Guarantee is a tool with great potential to promote youth employment also against the social consequences of the Covid-19 crisis. But it can only be successful if the evaluation of the current programme is taken into account and if the sectorial, national, and Europeans social partners are involved in its design, implementation and reporting of its future version it.

Sustainability: the #EU_SDG8i will be supporting the ETUC political priorities and demands for the Semester cycles. The index will be updated and new data processed to identify trends in sustainability and resilience paths of national economies. The #EU_SDG8i will analyse data and indicators for all the EU Countries plus the UK. Moreover, the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the EU Semester and RRF will be followed and assessed.

The assumption is that production (GDP), well-being and sustainability as areas of statistical activity only partially overlap with each other. This implies that no single framework can bring the three aspects together, and that the best approach is to identify some indicators pertaining to each area and to investigate their possible relations.